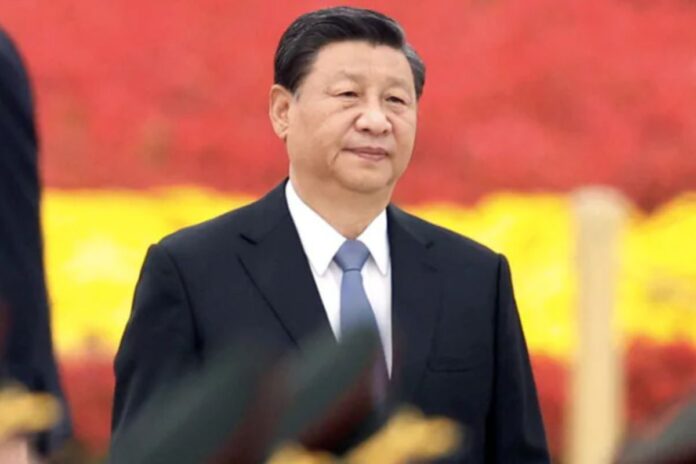

China builds new prisons as President Xi Jinping intensifies his crackdown on corruption. Over 200 specialised detention facilities, known as “liuzhi” centres, have been constructed or expanded across China. These centres are designed to hold suspects for up to six months without access to legal counsel or family visits. The centres have been a key component of Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign, which has been a hallmark of his leadership since he assumed power in 2012.

China Builds New Prisons to Support Anti-Corruption Campaign

China’s aggressive expansion of the liuzhi detention system has gained attention worldwide. These facilities, operational since 2018, are a replacement for the controversial “shuanggui” system, which had been widely criticised for its reports of torture and human rights abuses. The liuzhi centres are designed to detain individuals suspected of corruption, including Communist Party officials, civil servants, public institution managers, and businessmen accused of bribery. These centres are also used to detain those exercising public power, expanding the net of suspects beyond party members.

The centres have been purposefully designed with padded surfaces, round-the-clock guards, and surveillance cameras to monitor detainees. These harsh conditions aim to prevent detainees from harming themselves and ensure they remain under constant surveillance. Detainees can spend months without any access to their families or legal representatives, leaving them vulnerable to mistreatment and forced confessions.

Expansion of Liuzhi Centres Post-Pandemic

Between 2017 and November 2024, China has built or expanded over 218 liuzhi centres, with the construction effort intensifying after the COVID-19 pandemic. These centres have become increasingly widespread across the country, part of the government’s broader strategy to combat graft. Critics argue that these facilities allow local authorities and anti-graft agencies to abuse their power, detaining business leaders and public figures on questionable charges to extract confessions or bribes.

Among the high-profile cases related to these facilities are billionaire investment banker Bao Fan and former soccer star Li Tie, who was sentenced to 20 years in prison for corruption. These cases highlight the growing reach of the government’s anti-corruption efforts, which have expanded beyond the Communist Party to include individuals in various sectors of public life.

Criticism and Human Rights Concerns

Despite the government’s claims that these centres are essential for tackling corruption, human rights groups and critics have raised concerns about the treatment of detainees. A lawyer representing officials in corruption cases spoke to CNN, alleging that many detainees face extreme psychological pressure, threats, and torture. “Most succumb to the agony,” the lawyer said, detailing how detainees are often forced to endure sleep deprivation or long hours of forced sitting, leading to significant physical and mental suffering.

In one shocking account, former official Chen Jianjun described his six-month detention in a liuzhi centre, where he was subjected to grueling conditions such as forced upright sitting for 18 hours daily. His testimony, shared by his daughter, included sketches of his suffering on toilet paper.

The government has established strict construction rules for these centres and plans to build more facilities between 2023 and 2027. However, local anti-graft agencies are accused of abusing their power to target businesspeople and other individuals on false charges.

A proposed amendment to China’s national supervision law has stirred debate by extending the maximum detention period from six to eight months while maintaining restrictions on legal access during the liuzhi process. This move has faced backlash from critics who argue that the lack of legal safeguards will further expose detainees to mistreatment.