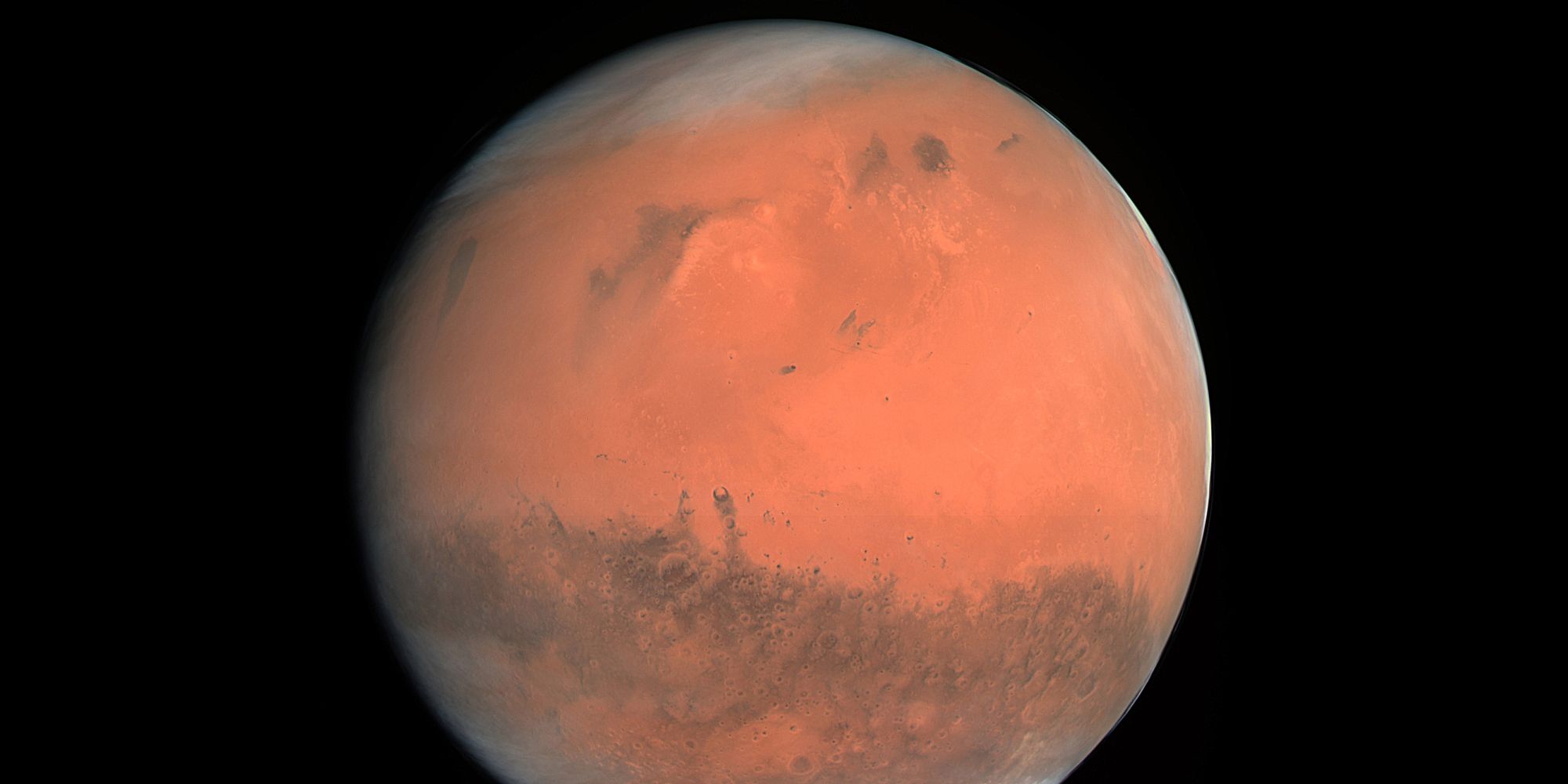

For centuries, the Red Planet has captivated human imagination. Its distinct reddish appearance has been a subject of wonder and speculation. Ancient civilizations named it after their deities of war, inspired by its blood-like color. However, recent scientific revelations have turned our understanding of Mars’ iconic hue on its head.

A groundbreaking study suggests that the planet’s redness is not due to dry, rust-like minerals as previously believed, but rather a water-rich iron mineral known as ferrihydrite. This discovery not only redefines our perception of Mars’ surface but also hints at a time when the planet was abundant with liquid water, potentially supporting life.

The Traditional Belief: Hematite and a Dry Mars

For decades, scientists posited that Mars’ red color stemmed from the presence of hematite, a common iron oxide on Earth. Hematite forms under dry conditions and was thought to cover the Martian surface, giving it its characteristic color. This theory aligned with the notion of Mars as a cold, arid planet, with its water reserves locked away in polar ice caps or existing as vapor in the thin atmosphere.

The hematite hypothesis was supported by spectral analyses from various Mars missions. Instruments aboard orbiters and rovers detected iron oxides on the surface, and hematite seemed a plausible match. However, this explanation left gaps in our understanding, especially concerning Mars’ climatic history and the apparent signs of ancient water flows observed in valley networks and outflow channels.

The New Revelation: Ferrihydrite and a Wet Mars

A recent study led by researchers from Brown University and the University of Bern has challenged the long-standing hematite theory. Published in Nature Communications, the research presents compelling evidence that ferrihydrite, a water-rich iron mineral, is the primary contributor to Mars’ red dust. Unlike hematite, ferrihydrite forms rapidly in the presence of cool, liquid water, suggesting that Mars once had a much wetter environment than previously thought.

The team arrived at this conclusion by meticulously analyzing data from multiple Mars missions, including NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and the European Space Agency’s Mars Express and Trace Gas Orbiter. These spacecraft provided detailed spectral data of the Martian surface, which the researchers compared to laboratory simulations. By recreating Martian dust in the lab, they found that mixtures containing ferrihydrite and basalt closely matched the spectral characteristics observed on Mars. This groundbreaking approach offered a fresh perspective on the planet’s mineral composition and its climatic history.

Implications for Mars’ Climatic History

The presence of ferrihydrite on Mars has profound implications for our understanding of the planet’s past. Ferrihydrite typically forms in aqueous environments, indicating that liquid water was once prevalent on Mars’ surface. This challenges the previous notion of a predominantly dry Martian history and suggests that the planet underwent significant climatic shifts.

The formation of ferrihydrite points to a period when Mars had a thicker atmosphere capable of sustaining liquid water. This era likely featured rivers, lakes, and possibly even oceans, creating conditions that could have been conducive to life. Over time, as the planet’s atmosphere thinned and temperatures dropped, Mars transitioned to the cold, arid world we observe today. The ferrihydrite present in the dust serves as a relic of this ancient, wetter epoch, offering clues about the planet’s environmental evolution.

The Role of Martian Dust in Preserving History

Martian dust plays a crucial role in preserving the planet’s geological and climatic history. Composed of fine particles, this dust blankets the surface, influencing both the planet’s appearance and its atmospheric dynamics. The discovery of ferrihydrite within this dust suggests that the processes leading to its formation occurred billions of years ago when liquid water was abundant.

As Martian winds eroded ferrihydrite-rich rocks, they generated the fine dust particles that now cover the planet. This continuous process has distributed the mineral across Mars, embedding a record of the planet’s wetter past within its dusty veneer. Studying this dust not only unravels the mysteries of Mars’ red color but also provides insights into the environmental conditions that prevailed during its formative years.

Laboratory Simulations: Recreating Martian Conditions on Earth

To substantiate their findings, the research team conducted innovative laboratory experiments designed to replicate Martian conditions. They synthesized ferrihydrite and basalt mixtures, grinding them into fine powders to match the particle size of Martian dust—approximately one-hundredth the diameter of a human hair. These samples were then subjected to spectral analysis under controlled conditions that mimicked the Martian environment.

The results demonstrated that the ferrihydrite-basalt mixtures closely resembled the spectral data obtained from Mars missions. This congruence provided robust evidence supporting the hypothesis that ferrihydrite is a significant component of Martian dust. These laboratory simulations bridged the gap between remote sensing observations and mineralogical analyses, offering a tangible link to Mars’ aqueous history.

Broader Implications for Mars Exploration

This paradigm shift in understanding Mars’ red coloration has far-reaching implications for future exploration and the search for past life. The presence of ferrihydrite suggests that Mars had a cool, wet climate capable of supporting liquid water, a critical ingredient for life as we know it. This enhances the planet’s potential for past habitability and directs future missions to focus on regions where ferrihydrite and other aqueous minerals are prevalent.

Upcoming missions, such as NASA’s Perseverance rover and the planned Mars Sample Return campaign, are poised to delve deeper into this mystery. By analyzing samples directly from the Martian surface, scientists hope to confirm the presence of ferrihydrite and unravel the planet’s climatic history with greater precision. These endeavors aim to answer fundamental questions about Mars’ potential to have harbored life and guide strategies for future human exploration.

Conclusion: Redefining the Red Planet

The discovery that ferrihydrite, a water-rich iron mineral, is responsible for Mars’ red color fundamentally changes our understanding of the planet’s past. For decades, scientists believed that hematite, a dry iron oxide, was the main cause of the planet’s distinctive hue. However, new research suggests that Mars’ dusty red surface is a direct result of past interactions between iron and water—a revelation that has far-reaching implications for planetary science, Mars exploration, and even the search for extraterrestrial life.

This breakthrough reinforces the idea that Mars was once a wet world, with conditions potentially suitable for life. The presence of ferrihydrite suggests a time when water flowed freely, forming rivers, lakes, and possibly even oceans. Over billions of years, as Mars’ atmosphere thinned and water disappeared, the iron within Martian rocks reacted with water and oxygen, creating ferrihydrite-rich dust that now covers the entire planet.

These findings reshape the way we look at Mars, not as a perpetually dry and barren world but as a planet that underwent a dramatic transformation from a wet, life-supporting environment to the cold desert we see today. More importantly, this research provides new directions for future Mars missions. Understanding the history of water on Mars is critical for determining whether the planet ever supported microbial life—and whether life could still exist beneath its surface today.

With missions like NASA’s Perseverance rover and the upcoming Mars Sample Return campaign, scientists are poised to analyze Martian dust and rocks more closely than ever before. These studies could **confirm the presence