Recent archaeological findings in Saudi Arabia have brought to light a fascinating glimpse into the region’s past, revealing how ancient societies transitioned from nomadic lifestyles to settled urban communities. The discovery of a 4,000-year-old fortified town, hidden in an oasis northwest of the Arabian Peninsula, illustrates the significant changes underway during the early Bronze Age. This town, now known as al-Natah, was unearthed beneath the lush oasis of Khaybar, surrounded by the arid deserts of modern-day Saudi Arabia. The oasis had long concealed the town’s remains, sheltering them from the elements and illegal excavations.

French archaeologist Guillaume Charloux and his team made this incredible discovery, which was first hinted at by the identification of a massive, 14.5-kilometer-long ancient wall in the area. The recent study, published in the journal PLOS One, provides convincing evidence that these ramparts surrounded a thriving community, indicating organized urban life. The large town is believed to have been home to around 500 inhabitants and was constructed approximately in 2,400 BC, during the early stages of the Bronze Age. It appears that al-Natah was abandoned around 1,000 years later, though the reasons for its desertion remain unknown, as Charloux explained.

During the time of al-Natah’s construction, urban centers were flourishing in the Levant, a region that stretched along the Mediterranean Sea and included parts of modern-day Syria, Lebanon, and Jordan. However, the northwest region of the Arabian Peninsula was long thought to be largely a barren desert, inhabited by pastoral nomads and known mostly for its numerous burial sites. This perception changed dramatically about 15 years ago, when archaeologists discovered Bronze Age ramparts in Tayma, another oasis to the north of Khaybar. This pivotal discovery encouraged archaeologists to take a closer look at other oases in the region, including Khaybar, eventually leading to the unearthing of al-Natah.

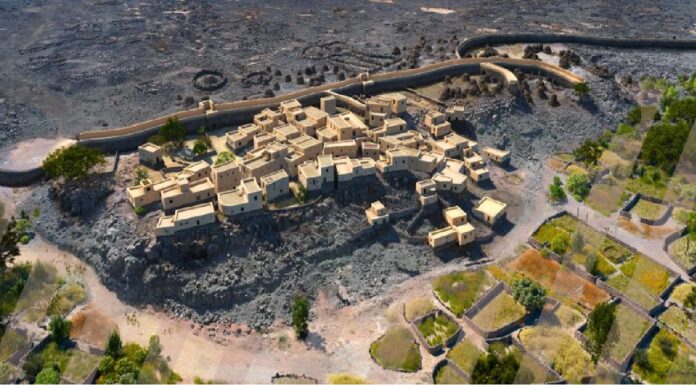

The unique landscape played an essential role in preserving the town. The walls of al-Natah were concealed beneath layers of black volcanic basalt, which not only camouflaged the site but also protected it from illegal excavations and looting. Observing the site from an aerial perspective allowed archaeologists to identify potential pathways and the foundations of structures, guiding them to where they should begin excavating. What they discovered were well-built foundations, sturdy enough to support at least one or two-story buildings. Though much more work is needed to fully understand the site, initial findings have provided valuable insights into the town’s layout and history.

Al-Natah spanned an area of around 2.6 hectares and consisted of roughly 50 houses clustered on a hill, surrounded by its own defensive wall. Inside a necropolis, the researchers uncovered tombs that contained a variety of intriguing artifacts, including metal weapons such as axes and daggers. Additionally, they found agate stones, suggesting that this society possessed a level of technological sophistication and wealth. The presence of pottery, characterized by its simplicity and elegance, indicates a relatively egalitarian society. As Charloux noted, the ceramics were “very pretty but very simple,” highlighting a culture that may have valued function as much as aesthetics.

The size and scale of the town’s fortifications, which included ramparts that could reach up to five meters in height, suggest that al-Natah may have been a center of authority for the surrounding region. These findings indicate a gradual shift towards more permanent and organized communities, a process that the researchers refer to as “slow urbanism.” This transition marked the movement from a nomadic, pastoral lifestyle to one based in fortified settlements. The researchers speculate that these fortified oases may have interacted and traded with one another, creating a network of contacts that eventually facilitated the famous “incense route,” which carried valuable commodities like spices, frankincense, and myrrh from southern Arabia to the Mediterranean.

While al-Natah was small compared to the grand cities of Mesopotamia or Egypt, it represents an alternative path towards urbanization that was unique to the northwest of Arabia. Unlike the rapid development of sprawling city-states, this “slow urbanism” was more modest, developing at a pace that suited the challenging desert environment. It reflects a form of community building that was deeply adapted to the specific conditions of the Arabian Peninsula, where life required resilience, resourcefulness, and adaptability.

The discovery of al-Natah offers a remarkable window into the past, challenging previous assumptions about the Arabian Peninsula during the Bronze Age. It suggests that even in the vast stretches of desert, human societies were experimenting with new ways of living, forming settled communities, and laying the foundations for more complex urban systems. This fortified town is a testament to the ingenuity of ancient peoples and their ability to adapt to and flourish in a challenging environment.